Tags

Anglican, Australian Digger, Ballarat, Barkly Street, Canberra, First World War, Frank Warner, Ipswich Q, Mervyn Napier Waller, Methodist, Queensland, University of Melbourne, Victoria, William Bustard

Soon after the first deaths on the battlefields of France and Belgium in 1914, families sought ways to ensure that their sons, husbands and fathers would be honoured and remembered. The ‘commemoration movement’ began as communities organised honour rolls, avenues of trees, arches, obelisks and stone soldiers in parks, crossroads and town centres, where ‘their name liveth for evermore’.[1]

Although less visible than public monuments, hundreds of stained glass memorial windows were quietly installed by grieving families to honour their lost loved ones, mostly in churches and chapels, in the decades that followed the First World War.

The most widespread subjects for memorial windows were saints and martyrs of the church, particularly St Alban, proto-martyr of the British Church, and Warrior Saints, St Michael and St George. As this war was fought under the banner of God, King and Empire, it is not surprising that St George, with a long and illustrious history as patron saint of England and the Order of the Garter and, from the late nineteenth century, as a symbol of British Imperialism, was most popular of all. After 1914, he symbolised the contemporary fighter for a just cause, chivalrous protector of the weak, and was generally depicted with the slain dragon at his feet, a powerful symbol of defeat over the enemy.

In the immediate post-war years, the figure of the Australian soldier was not seen in stained glass, but the gradual secularisation of Australian society that began during the war extended, somewhat unexpectedly, into the church. Not only was the image of the ‘digger’ accepted as a subject for stained glass, but also the Australian Military Forces badge, rifles and other symbols of war were additions to religious and secular windows throughout the 1920s and beyond.

Ipswich Soldier’s Memorial Hall, Qld

With due ceremony, General Sir William Birdwood laid the foundation stone of the Ipswich Soldiers’ Memorial Hall on 4 May 1920 and the grand three-storey building was officially opened on 26 November of the following year by the Governor of Queensland, Sir Matthew Nathan.[2]

Ipswich Soldiers’ Memorial Hall, Nicholas Street, Ipswich built in 1920-21 on the site of the old pump yard in Nicholas Park. Photograph: Darling Downs Gazette, 30 November 1921.

Ipswich Soldiers’ Memorial Hall, Nicholas Street, Ipswich built in 1920-21 on the site of the old pump yard in Nicholas Park. Photograph: Darling Downs Gazette, 30 November 1921.

The interior was quite splendid with offices, a library, recreation rooms and other amenities, built around a lofty galleried-hall that was naturally lit through the glass-domed roof. A marble ‘In Memoriam’ tablet inscribed with 153 names was accompanied by two silky oak honour boards holding the names of a thousand or more Ipswich men who served their King and Country.[3] But when the Hall opened in 1921 there was no stained-glass memorial window.[4] It was not unveiled until November 1922 when the Governor travelled to Ipswich once again to perform the ceremony of removing the Union Jack from its face ‘in the presence of a large number of relatives of deceased soldiers and friends’.[5]

Caption: William Bustard/RS Exton and Company Limited, Ipswich Soldiers’ Memorial stained glass window, 1922.

Caption: William Bustard/RS Exton and Company Limited, Ipswich Soldiers’ Memorial stained glass window, 1922.

Once unveiled, the hemispherical window revealed a most unusual tableau, as described in the Queensland Times the following day.

The central feature of the design is a figure of St. Michael, representing the Angel of Victory, with outspread wings embracing four soldier figures, representing the 9th, 15th and 26th Battalions and 5th Light Horse. He is shown standing on a globe representing the earth, with the crushed German Eagle lying at the base and in his hands he is holding a sheathed sword and the Palm of Victory. The field of Flanders is shown in the background, with scarlet poppies and crosses while a band of cherubs forms a valuable line in the design. The whole is encompassed in a border of grape vine, symbolising life. A valuable feature of the colouring is the richness of the ruby robe of St Michael, which comprises the use of four varieties of antique ruby [glass], and the beautiful blending of colours in the wings ranging from rich blues to green, brown and yellows…[6]

The window came from the firm RS Exton and Company Limited, Brisbane and was designed by artist, William Bustard (1894-1973) under the supervision of Charles H Lancaster (1886-1959), also an artist and head of the stained-glass department. It must have been one of Bustard’s earliest designs for the firm as he had only arrived in Australia from England in 1921, choosing to emigrate after a stint in the (British Army) Royal Medical Corps during the First World War where he served in Greece and Italy. Bustard showed his ability to use coloured glass to great effect, setting the figure of St Michael ablaze as noted in the press release, which created a dynamic contrast to the sombre khaki of the quiet soldiers. The multiple shades of brown ensured that even these uniforms do not appear drab while signalling the solemnity of the scene. The soldiers’ units can be identified from their dress, various trappings and colour patches set high on the arms of the uniforms. To border his design, Bustard used a wide grapevine device, a decorative symbol of Christ’s sacrifice and a new introduction to Australian stained glass, although he would have been aware of its use as a secular emblem from European design journals.[7]

Funds for such a dramatic addition to the Soldiers’ Memorial Hall were raised by a dedicated group of women, the Ipswich Train Tea Society, led by its President, Mrs Elizabeth Cameron. Throughout the war and during the period afterwards when the men were repatriated home, the small band of Ipswich women met every troop train, no matter what time it arrived, offering free refreshments to the estimated 60 000 men who came and went through Ipswich. [8] No public appeals were made throughout the war but later they assisted the Hall building fund by organising numerous events, and afterwards ‘patriotic entertainments’ to raise enough money for the commemorative window. Their role is recognised by a plaque that reads:

‘This window is erected by the Ipswich Train Tea Society and all the little children who helped them. In grateful memory of the men who gave their lives to keep our Empire, liberty and homes inviolate. Ipswich, 30 November 1922.’

Although the window was in a secular setting, it had an obvious religious connection through the decorative border, the band of cherubim and primary focus on St Michael. The Archangel was accepted as a warrior saint in different faiths – adopted by Christianity from the Jewish faith where he is seen as their guardian angel. He is also represented as the weigher of souls, measuring good and evil at the Last Judgement.

Melbourne Teachers’ College, Vic.

No such religious connotations can be made with a second secular stained-glass window, which was installed in the Lecture Hall of the Melbourne Teacher’s College (now the 1988 Building, University of Melbourne) in 1920. Here, the robust figure of the Australian digger fills the opening of the central of three windows, thrusting his rifle as if preparing to go forward into battle. Behind him a voluminous Australian flag billows out, although at first glance it seems to be the Union Jack until one realises that stars of the Southern Cross appear at either side of the figure. The round head of the window was filled with a pared-back version of the Australian Commonwealth Military Forces badge, giving the digger the appearance of a secular saint. The outer lights of the window served as an Honour Roll, in which the 39 men who paid the Supreme Sacrifice were identified in a separate roll, as well as the 190 who enlisted and returned.[9]

William Wheildon/George Dancey for Brooks, Robinson & Co., Lecture Hall, Melbourne Teachers’ College, now the 1888 Building, University of Melbourne, 1920.

William Wheildon/George Dancey for Brooks, Robinson & Co., Lecture Hall, Melbourne Teachers’ College, now the 1888 Building, University of Melbourne, 1920.

The commission was carried out by the prominent Melbourne firm, Brooks, Robinson & Co and placed in the capable hands of William Wheildon (1873-1941), head of the stained-glass department.

At first he thought the central figure should be more symbolic – a medieval knight, a Roman soldier, a figure representing courage – but in the end he confessed there was no reason why an Australian soldier could not express all the ideas suggested.[10]

The larger-than-life figure was drawn up by George Henry Dancey (1865-1922). It is not known who proposed the unusual (if not at that time, radical) idea for the very human Australian soldier instead of a symbolic or traditional figure but possibly it was Dr Smythe, head of the College, who was fiercely proud of all the teachers who enlisted. Throughout the war years he kept current students aware of the men’s experiences and wrote regularly to his former charges. At the unveiling ceremony in September 1920, he noted that the first soldier-teacher died on 27 April 1915 and the last was killed in action in the final engagement of the war, at Montbrehain on the Hindenburg line on 5 October 1918.[11]

The window was only one part of the Teachers’ College memorial and at either side of it a large tablet pictured small identified images of each man and the two nurses who enlisted, each painted on a vitreous tile about the size of a carte de visite.[12] Individually painted from photographs by freelance artist, Vincent Brun for Brooks, Robinson, the tiles were then kiln-fired to make the image permanent before they were cemented together like a mosaic in a process known as Opus Sectile.

Sometime in the 1970s, when the old Lecture Hall was converted into the Gryphon Gallery, the tablets were relocated elsewhere in the building and the window boarded up. It was indicative of a lack of interest in a far-distant war fought five decades earlier that no outcry accompanied these changes. At Ipswich, a comparable lack of interest in commemoration saw the removal of the memorial but it was not hidden. Instead it was installed in a light box inside the building, powered by fluorescent tubes that created vertical green stripes of light (if and when all tubes were working).

Fortunately, the importance and value of these significant memorials has been reconsidered and recognised and both have been brought into the light again; the shuttering is long gone at Melbourne Teacher’s College and the Ipswich window once again graces the façade of the Soldiers’ Hall where its colour and meaning can be fully appreciated.[13]

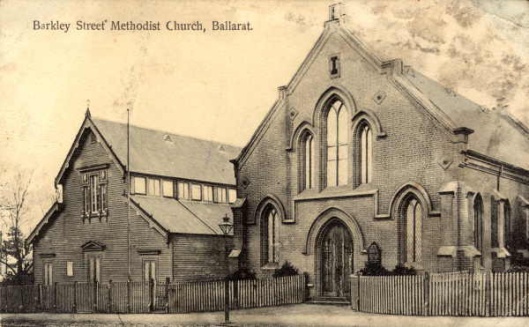

Methodist Church, Ballarat, Vic.

The first known ‘Digger’ window to be erected in any Australian church was for a Methodist Church, Ballarat, a three-light window that filled the openings above the gallery and facing Barkly Street.

Barkly Street Methodist Church, Ballarat, c1910. Ten years later the war memorial window would be inserted into the three lights facing the street.

Barkly Street Methodist Church, Ballarat, c1910. Ten years later the war memorial window would be inserted into the three lights facing the street.

In March 1920, the Ballarat Star reported the unveiling ceremony in detail and noted that ‘the windows are said to be unique of their kind in Victoria, if not Australia’.

The central light of the three holds the figure of the Australian digger, his bare head bowed over a mate’s fresh grave, marked by a makeshift cross, broken sword and wheel that symbolise his earthly war is over and a life eternal awaits him. Behind the soldier the battle continues to rage in almost darkness amid blackened forest remnants and bursting gun fire. The three lights together tell the story of all 24 men of the congregation who died in war: the trumpets in the left hand light represent the “Call to Arms’, the grave scene represents ‘Sacrifice’ and the dove in the right hand light symbolises ‘Peace’.

Caption: Frank Warner/Fisher & Co Pty Ltd, War Memorial, Barkly Street Methodist Church, Ballarat, 1920.

Caption: Frank Warner/Fisher & Co Pty Ltd, War Memorial, Barkly Street Methodist Church, Ballarat, 1920.

To commit to such a large and expensive memorial was a huge undertaking, but in 1919 the Barkly Street Young Men’s Club took on the task and asked leave to raise funds to pay for the project.[14] (It is worth mentioning that the cost, which included transport, installation and the wire protective screens, cost 171 pounds. It today’s terms this is likely to be around $60,000!)

The commission was undertaken by the small Melbourne firm, Fisher & Co Pty Ltd of Watson’s Place, a business set up by Auguste Fischer (1860-1916), an English artist who came to Australia in the 1880s.[15] Anti-German feeling increased during the war and the name of the firm changed, possibly around the time of Fischer’s unexpected death in 1916. Although the business was purchased by Brooks, Robinson & Co, Fischer’s draughtsman Frank Warner is believed to have continued to operate the studio for some years and to have been the designer of the Barkly Street war memorial.

From this time onwards the Australian soldier appeared in stained glass commemorative windows in most Protestant denominations.[16] Among the churches were St George’s Presbyterian, Geelong (1921), St George’s Anglican, Malvern (1926), St James’ Anglican, Heyfield (1921) all in Victoria; St John’s Anglican, Buckland Tas (1921); St James’s Anglican, Toowoomba Qld (1922); and St Mark’s Anglican, Nyngan NSW (1926). These later installations differ in every way from the Barkly Street soldier pictured grieving at the loss of a comrade and validates the Ballarat Star’s claim to the Barkly Street window’s ‘uniqueness’. It remains as the sole example of a digger in a Methodist church window.

Australian War Memorial, Canberra ACT.

The last great secular space to include the digger in stained glass was Hall of Memory at the Australian War Memorial, Canberra. The scheme of three, five light windows evolved over years, with the Second World War intervening before the fourteen representations of the Australian serviceman and one nurse of the First World War were finally unveiled in the 1950s.[17] Considered to be a masterpiece by Melbourne artist Mervyn Napier Waller, these larger-than-life figures combine secular subjects with Christian symbols, similarly to Bustard at Ipswich. Waller has woven a complex tapestry that combines the qualities of the fighting man, the First World War uniforms and equipment that symbolised their roles and skills within military forces with emblems of Australia, the Aurora Australis, the Southern Cross and the AIF Badge. Together they embody the Australian digger in stained glass.

Mervyn Napier Waller, detail, Hall of Memory, Australian War Memorial, Canberra ACT.

Anzac Day 2020

Australia, along with the rest of the world, is fighting a different battle to that faced in 1914, a microscopic organism instead vast armies and hideous weaponry. So, instead of coming together at Dawn Services here and overseas, marching in the streets to the drums of masses bands, or visiting a Shrine or Cenotaph to lay a wreath, we will remember in different and separate ways. We may be apart but, as always, – we will remember them.

Dawn, Mount Eliza, Victoria, 25 April 2020

[1] These words from Ecclesiastes 44:14 were selected to be inscribed in stone at all Commonwealth War Grave Cemeteries from 1915.

[2] Darling Downs Gazette, 30 November 1921, p. 7; Table Talk, 8 February 1923, p. 25.

[3] Darling Downs Gazette, 30 November 1921, p. 7.

[4] Reports at the time of opening in 1921 gave a figure of ‘nearly’ 1000 servicemen, but later reports indicate it had climbed to ‘a thousand or so’.

[5] Queensland Times, 1 December 1922, p. 4.

[6] Queensland Times, 1 December 1922, p. 4.

[7] Corner and Border Designs 1900, Pepin van Rooger, Amsterdam, 1900.

[8] Queensland Times, 19 August 1922, p. 10.

[9] Herald, 14 October 1919, p. 13.

[10] The Trainee, Vol VIV No 5, October 1920, pp. 8-9. Thanks to Bart Ziino and Jay Miller.

[11] Lieutenant John Foster Gear, 24 Battalion, KIA, 5 October 1918, had been awarded the Military Cross only one month earlier ‘for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty in charge of the brigade sniping section during an attack…’. NAA: B2455, Gear JF. The Australians were retired the following day and did not enter the front line again before the Armistice signing on 11 November 1918.

[12] It is highly likely that Brun painted the images of the soldiers and nurses from Algernon Drage’s photographs taken shortly after enlistment, of which 19 000 are now held in the Australian War Memorial collection.

[13] Brenton Waters, 9 November 2017. http://www.ipswichfirst.com.au/story-behind-ipswich-rsl-sub-branchs-memorial-window/

[14] Barkly Street Methodist Church archives, courtesy of Mr Lindsay Harley.

[15] He trained in stained glass in Warwickshire before working in London and travelled in Europe and America. National Archives of Australia MP 16/1/0, File No. 1914/3/521.

[16] The Catholic Church, which had a precedent for saints and biblical subjects maintained that practice.

[17] See Susan Kellett, ‘Truth and love: the windows of the Australian War Memorial’, Journal of Australian Studies, Vol 39, No 2, 2015, pp. 125-150.

Thanks for this interesting post. My great-grandfather was an Anzac padre.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Donald

Many thanks for your comment and I am delighted that you found the post of interest. I try to add an Anzac-related post on 25 April each year, and I was tempted to write about nurses, given of current pandemic that certainly had its parallels 100+ years ago. Padres are another group who do not always get a great deal of acknowledgement for their difficult work in war. There are a couple of books on theim and their work, which you may know about already. And there are a few stained glass windows that were installed in their honour, for instance Padre Gault (Methodist at Camberwell Vic,) and Bishop Long (Anglican at Newcastle and Grenfell NSW). Your great-grandfather undoubtedly had extraordinary experiences. If you were interested in telling more about him please email privately: bronwyn@glaasinc.com.au

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Bronwyn, thank you for this poignant and well researched article which brings to life the mood and sentiments of the time. It is still very sad that the town and country communities paid so much but would have gained so little from the distant World War. It is heartening to see that so many beautiful stained glass windows – so full of meaning, so visible but so fragile – have endured almost 100 years, and have found new appreciation in the eyes, hearts and minds of today’s community.

I also really enjoyed your 2018 article on the Broughton community stained glass window. I know the Kaniva district and can picture the vast wheat fields and eucalyptus- lined lanes which have not changed much in 100 years.

Thank you again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the feedback Michael. I maybe could have added that Ballarat’s Barkly Street Church closed and the whole site was sold to a developer – its carpark and access from two streets made it very saleable. The church is protected and far as I am aware the window remains intact but probably can only be seen by people who read this post.

Bronwyn

LikeLiked by 1 person

Bronwyn,

I have just read your marvellous account regarding the windows, there is no doubt you deserve all the accolades that come your way. Thank you for allowing me. The pleasure of a read.

Peter

LikeLiked by 1 person

Peter

Thank you for taking the time to comment on ‘The Australian Digger in Stained Glass’. It is not just the glorious windows but also the interesting stories of the people behind the making and donating, as well as those whom we remember.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A very interesting and captivating read Bronwyn. Thank you. It makes me want to visit all these sites- a good reason to get back on the road when we are allowed to.

I was pondering your drawing attention to the secularization of the images , from Christian warriors to explicit uniformed figures even explicit individuals. I wonder where we go from here, and imagine it will be into abstraction.

There is clearly a strong desire to memorialize even as there is a reduction and use of places which have innate meaning to people such as churches. Perhaps the advent of the roadside memorials to traffic accident victims is part of this.

I note we are about to spend $480 M on the renovation and expansion of the Canberra War Memorial and am hopeful that some of the $480 M will pass to a new generation of glass artists to offer their interpretations of the events

Keep up the fantastic work you do.

Martin

LikeLiked by 1 person

It would be great to see some glass installations (I hesitate to say ‘stained glass’ as it could take many forms these days, as you point to in your comment) in the new works as part of the Australian War Memorial redevelopment. Amazing to thank that Napier Waller’s figures are 60+ years old – they have worn well and will continue to do so. Thanks for taking time to comment – it is always appreciated and adds to the conversation.

Bronwyn

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Dr. Bronwyn Hughes,

In the past I received your posts via the Glaas Inc Research blog which were very interesting. Given your expertise in stained glass history in Australia, I was wondering if you would please be able to provide some advice on two stained glass panels ?

I’ve recently been contacted by a friend who now owns two stained glass panels (possibly window panels or internal door panels?) which came from a property called Pineleigh in Goulburn , New South Wales, built in 1873 by the Goulburn blacksmith Henry Monkley. The property was bought by the Sisters of St Joseph in 1929 and used as a Novitiate until 1970 when it was sold and became a private residence again.

I’m assuming that the glass panels – please see images attached- were installed in the chapel by the Sisters of St Joseph , when the nuns took over the property from 1929. There are no names or initials on the stained glass panels indicating a possible maker.

I was wondering if you may have some information about the glass panels in terms of their possible age , if they may represent particular Biblical stories or angels, and whether they are familiar in terms of a designer or maker? Any advice you could provide would be much appreciated.

I look forward to hearing from you and thanks for your assistance.

Regards,

Claire

Claire Baddeley

On Sat, Apr 25, 2020 at 9:48 AM glaas inc research wrote:

> Dr. Bronwyn Hughes OAM posted: “Soon after the first deaths on the > battlefields of France and Belgium in 1914, families sought ways to ensure > that their sons, husbands and fathers would be honoured and remembered. The > âcommemoration movementâ began as communities organised honour rolls,” >

LikeLike